This is an edited version of an essay written early this year. It's very long, so I will post the second part at a later date along with a bibliography.

In his famous essay ‘Art as Technique’, Victor Shklovsky proposes that ‘art exists that one may recover the sensation of life, it exists to make one feel things’ (16). This concept of art’s purpose is considered crucial, as Shklovsky has already described the increasingly ‘automatic’ nature of both language and perception (15). Formalists such as Shklovsky considered defamiliarizing techniques – the ability to make the familiar strange - in writing as a crucial means of combating this decline, and their ideas continue to be applicable to art across many mediums. Stanley Kubrick’s 2001: A Space Odyssey uses space as a backdrop against which aspects of our earthly existence are isolated and open to re-evaluation. One of its main pre-occupations is the question of how ‘human nature’ will alter in the future, expressing both scepticism and hope about man’s ability to retain his humanity in a world increasingly dominated by technology.

Kubrick’s film - while perhaps most remembered for its immaculate, clinical sets - begins with a completely different aesthetic. The ‘Dawn of Man’ sequence that begins the film simulates the natural landscape with a sense of awe and wonder, depicting the beauty of many disparate aspects of nature (an orange sky at sunset, a leopard with glowing eyes reclining next to its kill) with equal reverence. The match-cut from bone to space-ship that compresses a few million years of history into a fraction of a second marks a shift in the films’ focus from the natural world to the unnatural one. From this point on, nearly all of the interior sets are flawlessly white and clean. While this clinical perfection suggests a future that is unnatural and estranged from man’s origins, the photography of the sets nonetheless showcases them as examples of man’s capabilities. In a similar vein, the juxtaposition of footage of the space-ships drifting through the vacuum of space with classical music generates an air of pomp and grandeur, an atmosphere that contrasts sharply with what Piers Bizony refers to as ‘redundant’ dialogue scenes (16). The white sets act as plain backdrops against which traces of colour - the air stewardess’s pink uniforms, the red chairs in the lobby of the space hotel, the artificial food – seem shocking and garish.

Another contrast that arises from the film’s use of colour can be seen in the scenes that depict contact between the people in space and their families back on earth. When Floyd wishes his daughter happy birthday over a monitor, she is shown in a frilled, boldly patterned dress that clashes harshly with the sleek, monochromatic costumes worn by the space travellers. Similarly, the bright smiles and traditional clothing of Poole’s parents (who, in an interesting parallel to Floyd's scene with his daughter, are wishing him happy birthday from earth) make them seem like out-dated objects of ridicule, an impression reinforced by their son’s cold disinterest in their message.

The film places significant emphasis on the most mundane elements of everyday life, speculating about how they will have altered in the future. Footage of apes consuming raw, bloodied meat at the beginning of the film are paralleled by scenes that show people drinking their artificially coloured dinner through straws, and long periods of meditative silence are set against ones of empty, automatic chatter. In many ways, the film functions as a satire, with Philip Mather describing the irony of Floyd’s acting like a ‘bored businessman’ when surrounded by, what are for the audience, views of incredible, awe inspiring beauty (199). The resonance of such satire is reinforced by the film’s commitment to accuracy. Kubrick’s use of contrast and satire contrast are central to its thematic development, as Marcia Landy describes:

If ‘The Dawn of Man’ episode highlighted the solidity of the terrestrial terrain ... what is evident in [the untitled, middle segment of the film] is a loss of contact with the landscape and with the body expressed in the unsteady movement of humans and the restraints of communicability (92)

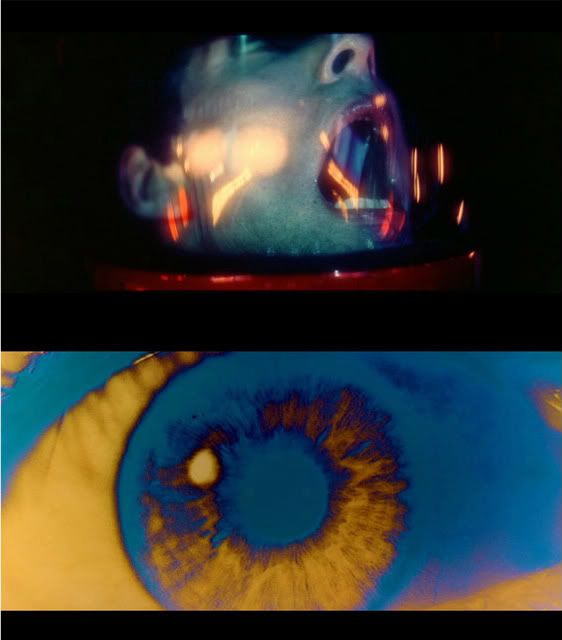

This estrangement of man from his origins is perhaps indicated most strongly by the aesthetics of the stargate sequence that comes towards the end of the film. Astronaut Dave Bowman’s horrified, pain-contorted face flashes on the screen in the midst of a bombardment of vividly coloured lights. In contrast to the more sedate pace of what has come previously, the lights displayed in the stargate sequence move with disorientating rapidity. There has been a change from a slow, careful pace to one of urgency. This frenzy of movement and colour is contrasted with the use of still reaction shots of Bowman’s face; ironically, at the time when he shows the most emotion he is denied expression through movement. The astronaut becomes a subliminal figure, a brief snapshot whose appearances are too sudden to be substantial. This reduction of Bowman’s role leaves the viewer to experience the sequence directly; they are denied the presence of a referential figure to direct their response. Mather describes the stargate sequence as an attempt to go ‘beyond the anthropomorphic limits of our imagination ... [and] represent the truly alien’, a fitting description that takes into account the almost complete lack of human presence in the scene (187).

The defamiliarizing effect of the stargate sequence is intensified by the shots of artificially coloured landscapes that follow it. The choice of footage parallels that which appears at the beginning of the film in that both show natural landscapes: mountains, seas and deserts. Yet the carefully considered framing and slow pace of the images featured in the ‘Dawn of Man’ sequence at the start of the film is exchanged for sweeping, high angle shots of the landscape that move at a relentless pace. The footage was subject to intense treatment in post-production – the shots appear in a variety of divergent, heavily saturated colours – which recreates the natural world as a bewildering, nightmarish presence that Bowman cannot look away from. The landscape footage is interspersed with extreme-close ups of Bowman’s eye as his pupil dilates and contracts, a choice of image that Mather suggests ‘emphasize[s] his status not only as the “looking subject” but also as victim’ (192). The claustrophobia and totality of experience implied by the intimate proximity of the shot can also extend to the viewer; the eye is isolated to such an extent that it becomes a symbol of the general viewing experience as much as it does of Bowman’s specifically. The astronaut’s eye functions as a stand-in for the viewer’s, representing the defamiliarizing effect of the film’s climatic scenes through its own radically altered state.

Essentially, defamiliarizing imagery is used in 2001 to jerk the viewer from a state of complacency, with garish colours and recurring imagery being used to make the viewer engage critically with the material being displayed. While the film places significant emphasis on the beauty and wonder of man’s technical capabilities, it also reminds the viewer of the necessity of remembering our origins.

No comments:

Post a Comment